News, ideas and everything in between (#3)

Social media licensing, 99 Speedmart's IPO and the case for Bursa Malaysia.

I was supposed to push this out Saturday but I had to pack in some additional information and that took some time. Apologies for the wait. But here it is. Slightly heavy on the business side this morning. But, as they say, better done than perfect.

You’re reading a free version of The Malaysianist, the newsletter on money and power by journalist, Emmanuel Samarathisa.

To keep this little corner of the internet going, grab an annual or monthly subscription.

There’s also the atas or founding member tier where you get all the perks of an annual subscription and more, such as the founder’s report that breaks down things like earnings and insight on running a newsletter project.

More importantly paid subscribers get ad-free exclusive content such as deep dives and Q&As. It’s the next best thing since avocado and toast.

Group subscriptions are on the table, too, if you’re mulling over bulk purchases for your organisation or family members.

In today’s edition:

👮 Can MCMC effectively regulate social media platforms?

📈 The minimart that is Malaysia’s next biggest IPO

🇲🇾 A case for listing on the local bourse

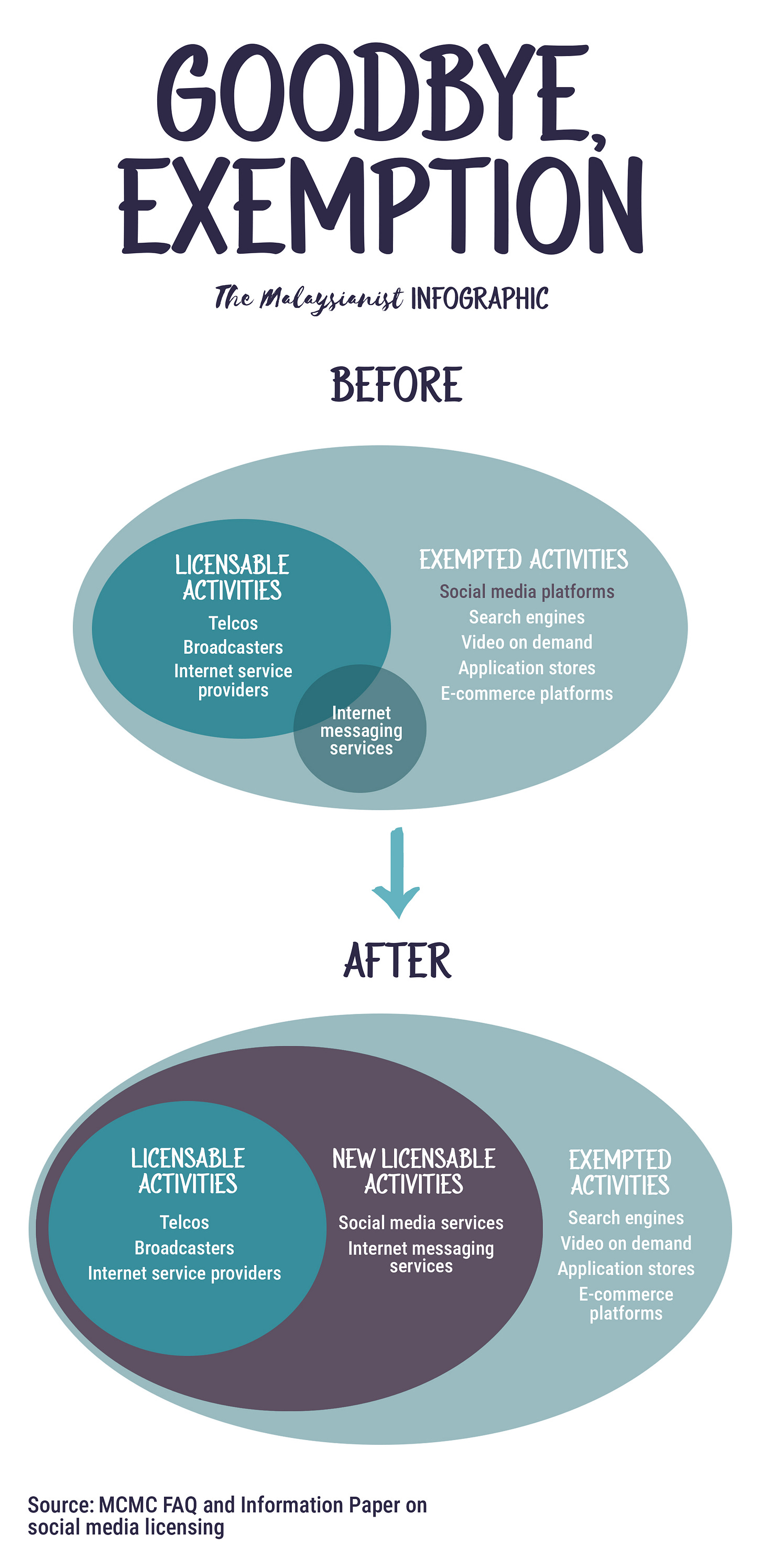

Malaysia’s internet regulator published two documents on social media licensing right on the August 1 deadline.

The documents, which are publicly available1, are close to what I ran in Tuesday’s newsletter. But the finalised versions are somewhat clearer.

For starters, MCMC defined the entities that would be regulated. Per the document:

The amended EO 2000 and LR 20002 define Internet messaging service and social media service as follows:

a. “Internet messaging service” means an applications service which utilises Internet access service that enables a user to communicate any form of messages with another user.

b. “social media service” means an applications service which utilises Internet access service that enables two or more users to create, upload, share, disseminate or modify content.

Unlike the EU and Indonesia, MCMC says that the licensing doesn’t stretch to “online services such as video on demand (VOD), search engines, application stores and e-commerce platforms”.

To be sure industry body Content Forum already published a content code for over-the-top service providers.

The country’s internet regulator, again, reiterated that the main agenda ostensibly is to curb online crime, from scams to illegal gambling, and cyberbullying.

The rest you’d know by now: social media platforms with 8 million registered users and above will need to register for a licence, the licence costs RM2,500 yearly, only platforms (not users) are subjected to the licensing, firms will need to incorporate an entity here but allowed to have 100% foreign ownership, and platforms will fall under the ambit of the MCMC and relevant laws.

More importantly social media platforms are under a grace period until January 1, 2025, to adjust and subject themselves to Malaysia’s newly enforced licensing requirements.

From the document, MCMC is trying to strike a conciliatory tone, especially “through a public consultation during the grace period”, where the agency would engage “all members of the public… as well as interested individuals” will be invited to provide feedback on the guidelines.

This is an ambitious claim. But, as it’s still early days, expect a lot of back-and-forth.

The proof of the pudding ultimately rests with MCMC and platforms, and to what extent both are open with their handling of problems on social media.

In MCMC’s case, it’d be whether the agency can keep to its word in providing that open forum for feedback. Also, being able to provide feedback can be an academic exercise — it doesn’t mean they are compelled to listen to suggestions from the public.

Terms like cyberbullying remain vague and prone to abuse as the interaction between platforms and MCMC over problematic postings happens away from public scrutiny.

The death of TikTok influencer Rajeswary Appahu, also known as Esha, has been used by proponents as an example of why platforms have grown too powerful and need to be reined in. Yet the same folk are silent on calling for better enforcement.

Rajeswary’s mother, R. Puspa, flagged a number of social media users, including Muslim preacher Zamri Vinoth and policewoman Sheila Sharon Steven Kumar, who made disparaging remarks about her daughter even after her death.

Puspa filed a police report, but no investigations have been made against them at the time of writing.

Online crime — from child pornography to animal and human trafficking — have been long standing problems. TikTok is courting plenty of flack. But other platforms, such as X, the home of pro-government diehards, are equally notorious.

Then there are politically loaded ones. Meta recently censored Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim’s tribute to the late Hamas chief Ismail Haniyeh.

Anwar took that to town. The Malaysian government demanded an explanation.

Communications Minister Fahmi Fadzil clarified that the decision didn’t come from Meta’s Southeast Asian office but higher-ups. He’ll be meeting with the firm’s representatives soon to sort out the matter.

While Minister Fahmi has come out to say that it isn’t the government’s intention to block access to platforms but to regulate them with safety of minors being top priority, MCMC’s documents does not rule out such an action:

17. What actions can be taken by MCMC against a licensed Service Provider for any breach of licence conditions and/or the conduct requirements?

MCMC will assess the nature of the breach including its severity, impact, and frequency as well as the compliance record of said Service Provider in deciding the appropriate action to be taken against them.

In such circumstances, MCMC can initiate actions ranging from administrative warning, issuance of compliance direction to rectify the breach, impose civil penalty or compound offences to proportionately deal with the breach.

In the most severe and grave nature of breach, MCMC can suspend access to said Service Provider’s platform; de-register of the ASP (C) licence; or commence prosecution.

There’s also the possible fines and jail time for errant platforms that fail to register for a licence. Per MCMC:

16. What if the services are being provided by the Service Providers without the required licence beginning 1st January 2025?

If any Service Provider operates without a licence beginning 1st January 2025, actions can be taken under section 126 of the CMA 1998.

If convicted, the Service Provider shall be liable to a fine not exceeding RM500,000 or five (5) years imprisonment, or both, and shall also be liable to a further fine of RM1,000 for every day or a part of a day during which the offence is continued after conviction.

Is that kind of enforcement on platforms really effective, you ask? Beats me. If X or Telegram don’t comply, who is the Malaysian government going to after and what is it really going to do?

And on scams and such, while MCMC has been going down hard on these things, bad actors still find ways of circumventing restrictions, because social media firms earn from advertising.

Platforms are powerful and command a wide influence, even in political discourse.

But, at the same time, while governments everywhere — not only Malaysia — wrestle with various ways to keep tech giants in check, there are concerns of government abuse.

Transparency, proper communications and generally good policymaking will go a long way. But these, too, are open to interpretation and somewhat in short supply over on this side of the globe.

The good news is, at least from a government standpoint, if things get too hot to handle, Malaysia can take inspiration from Turkey, which recently blocked Instagram for allegedly censoring postings of Haniyeh’s death.

Hopefully it doesn’t come down to that.

(The Malaysian government is sending a signal that as platforms are now required to incorporate here, there’ll be some corporate tax revenue. Then again, didn’t we bend over backwards when it came to incentives for Elon Musk’s Tesla and Starlink over a Zoom call?)

SPONSORED

Now is the time to launch your own startup. With years of experience and a drive to build a billion-dollar tech company, this is your call to finally take action and become the founder you’ve been thinking of.

Antler, a global early-stage VC, is calling on Malaysia's top talents to build the next billion-dollar tech company.

They invest in founders from day zero, backing the best minds to find co-founders, validate game-changing ideas and secure US$110,000 in pre-launch capital, with up to US$600,000 of early-stage funding in total.

Tell us how entrepreneurial you are and we’ll show you how to build and launch your company in 10 weeks. All we’re looking for are “just” your talent, passion, and commitment.

Ready to build the most defining companies of tomorrow?

The next big Malaysian IPO: a minimart

Malaysia’s 99 Speedmart is expected to list on September 9, according to a Reuters report, with the minimart chain looking to raise RM2.36 billion from its initial public offering (IPO) on the Bursa Malaysia.

If the listing materialises, and at that valuation, this could be Malaysia’s largest IPO in seven years. In 2017, South Korean petrochemicals giant Lotte Chemical Titan listed on the Bursa, raising RM3.77 billion.

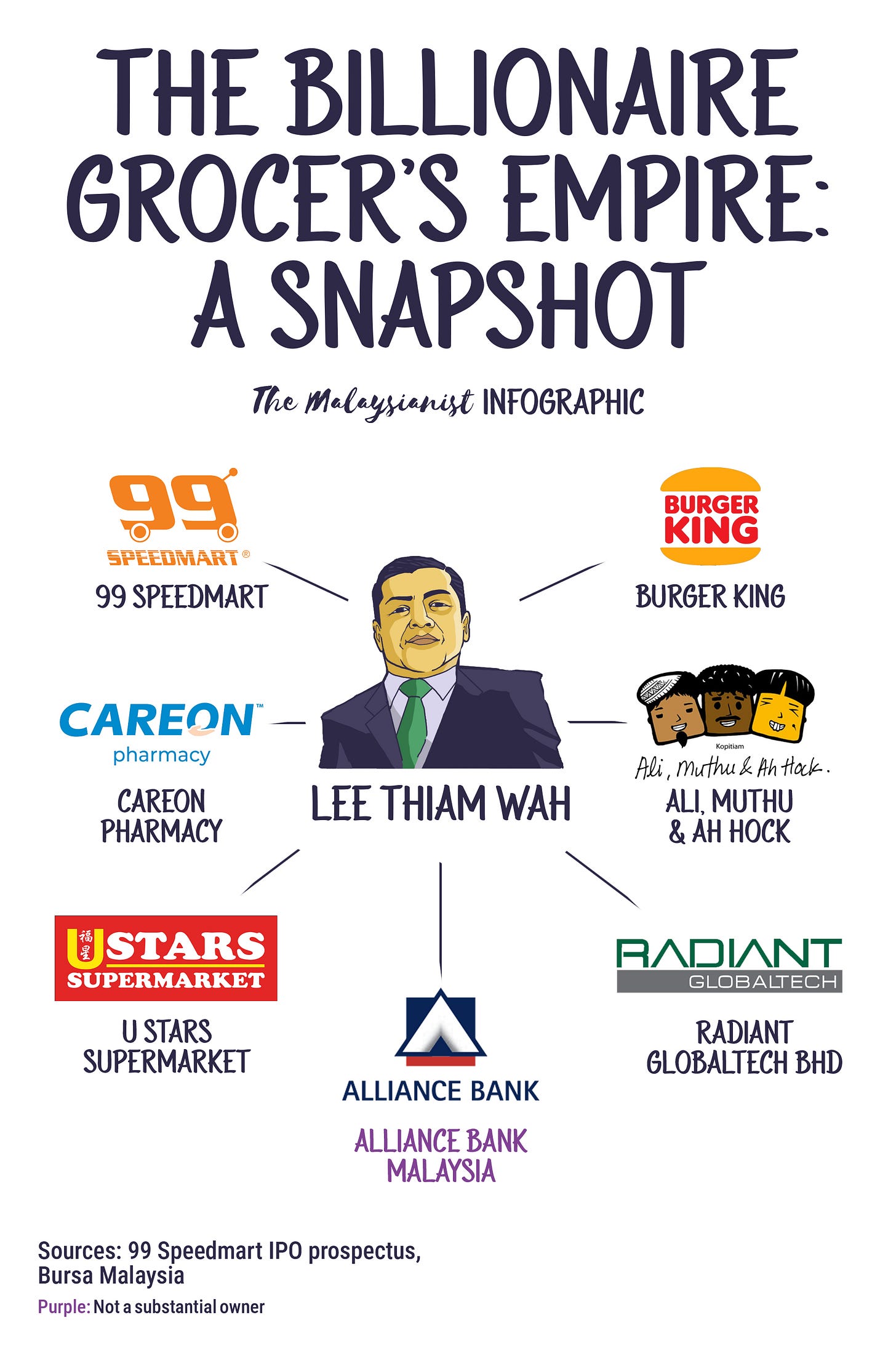

Entrepreneur Lee Thiam Wah founded 99 Speedmart in 1987. His rise to fame is in equal parts extraordinary as it is mysterious.

Lee began selling snacks by the kerbside to make ends meet when he was 14 years old. By the time he was 23 years old, Lee saved up RM17,000 to open a sundry shop called Hiap Hoe in Klang.

Five years later, Lee sold the shop for RM50,000 and with another RM30,000 loaned by his family and relatives, rolled the money to start Pasar Mini 99 in Klang.

Lee then opened a number of stores between 1992 and 1998 and, in 2000, renamed the chain 99 Speedmart.

The grocery business has been lucrative for Lee and his wife, who’s also his business partner.

The couple took home slightly more than RM1 billion in dividends across the last four financial years, according to 99 Speedmart’s draft prospectus.

In fact, the grocery chain catapulted Lee as a major corporate player, owning some of the country’s iconic brands such as the Burger King chain and the Ali, Muthu and Ah Hock franchise. He is also a minor shareholder in Bursa-listed Alliance Bank.

His ability to move millions was evidenced in the Burger King deal. In 2015, he paid RM74.6 million for the franchise and took it off Ekuinas’ hands.

The government-owned private equity firm invested RM146.4 million to get Burger King running but failed.

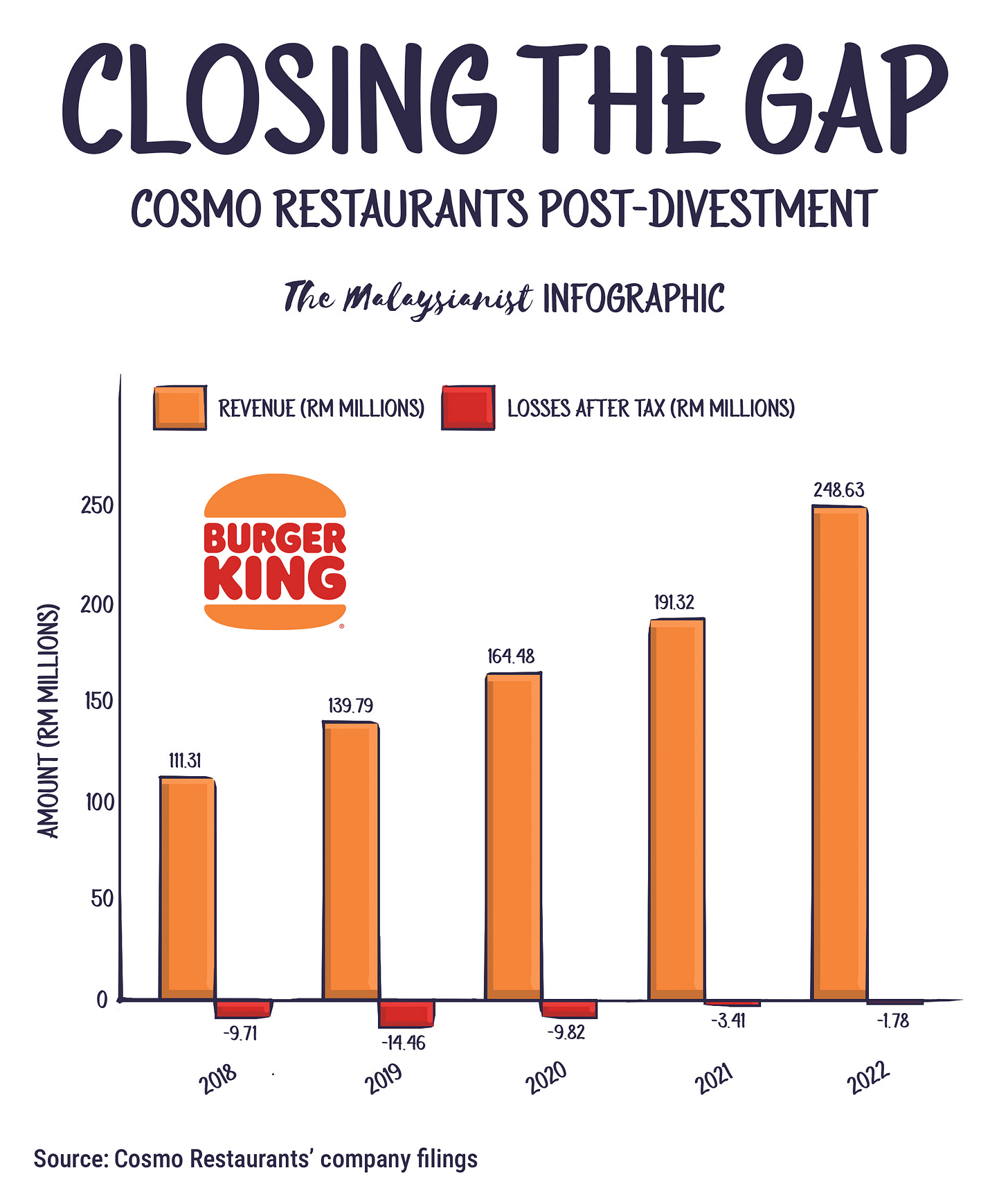

When Lee took over, the fast-food chain was bleeding. Burger King’s holding company, Cosmo Restaurants, is still loss-making but that has narrowed since Lee’s acquisition.

And his corporate footprint is remarkably different from his closest competitor, K. K. Lau, who runs the KK Mart convenience chain. Lau also claims to own a diversified range of businesses — from a coffee shop to cosmetics — but these are not as high-profiled as those under Lee’s belt.

Lee will be offering up a 17% stake or as much as 1.43 billion shares for its IPO. Proceeds will be for expansion, to set up distribution centres and purchase delivery trucks, among other things, and repay existing bank loans.

99 Speedmart is aiming to open on average 250 new outlets annually with an immediate target of around 3,000 outlets operating nationwide by the end of 2025.

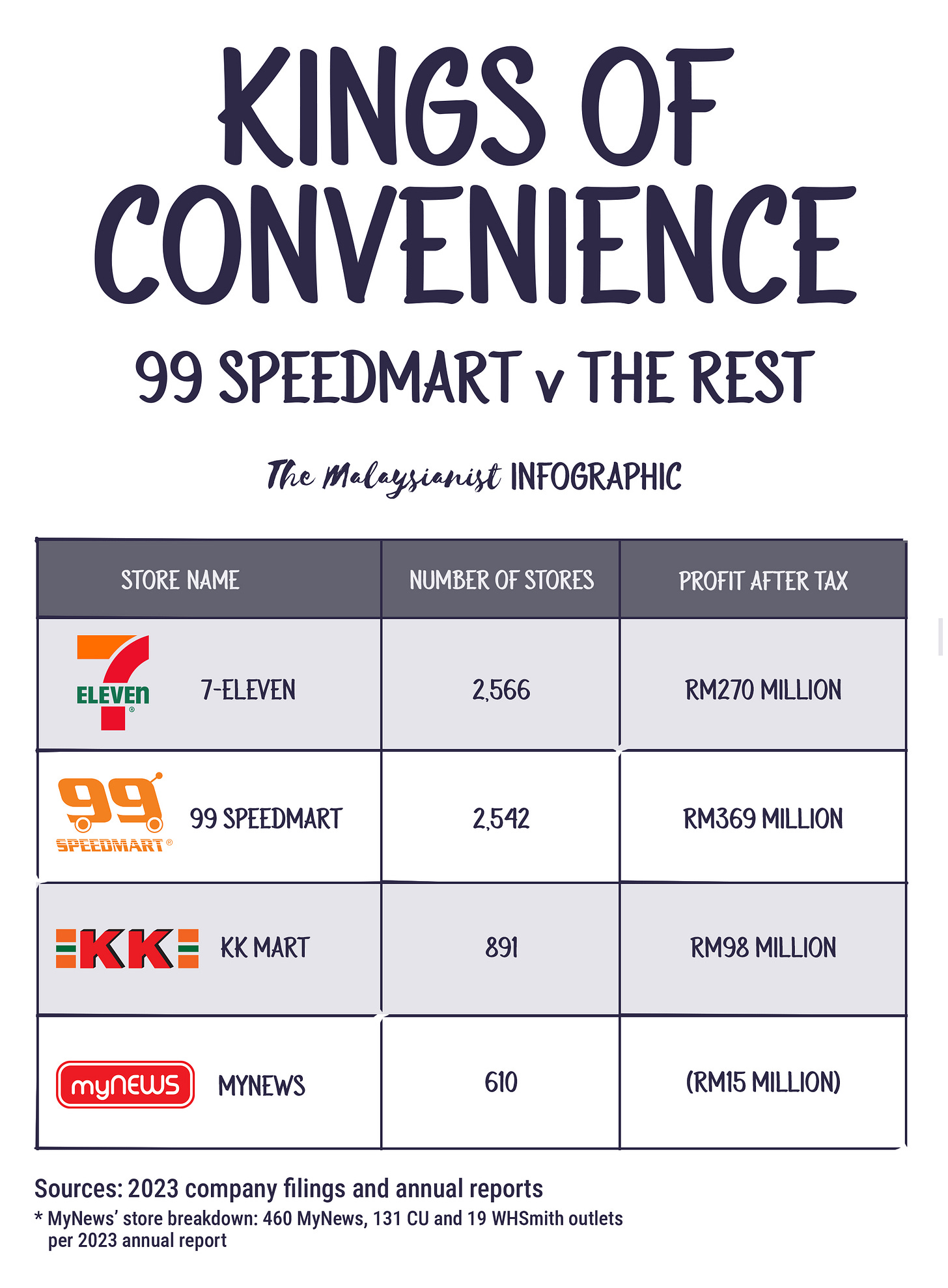

99 Speedmart currently operates 2,542 outlets across Malaysia and 19 distribution centres. That puts Lee’s grocery chain far above the competition, with only 7-Eleven as rivals3.

With a RM2.36 billion listing price tag, Reuters claimed 99 Speedmart could also be Southeast Asia’s largest IPO in over a year, since Indonesia’s Amman Mineral Internasional.

If the timing is right, Lee’s minimart empire could also put Malaysia on the largest-Southest-Asian-IPO list as most big-ticket ones over the past five years have been dominated by Thailand and Indonesia.

A local twist

Lately, Bursa Malaysia has been gaining some attention. There’s Deloitte’s mid-year report on Southeast Asian listings that provided a measured review of Malaysia’s performance vis-a-vis its peers.

There’s the Securities Commission’s initiatives such as the fast-tracked or accelerated transfer for companies to move from the ACE to the Main Market.

There’s also hype from the investment community, buoyed by foreign direct investment announcements, that tout the local bourse as a favourite for a listing or exit.

At the recently concluded Tech in Asia conference, Carsome chief Eric Cheng said he was mulling over a listing on the Bursa Malaysia as he believed the local bourse had an advantage.

Among other things, Malaysian retail investors understood Carsome, with some having used the used-car marketplace.

For tech listings the Nasdaq is usually the place to be. The US stock exchange provides a wider and diverse pool of investors, higher valuations and, more importantly, it caters to tech stocks.

That remains true for a select group of Malaysian companies. For instance, biotech group ALPS Global will be listing on the Nasdaq.

But there has been quite the push to go local with potential heavy hitters 99 Speedmart and telco U Mobile.

The latter has been eyeing an initial public offering (IPO), after its controlling shareholder Vincent Tan told Bloomberg that he rejected rival Maxis’ offer for an acquisition, and he would be opting for a listing, seeking a valuation of RM10 billion thereabouts.

Meanwhile, the Deloitte report contains some interesting observations.

On one hand, the report highlighted that for the first quarter of 2024, Malaysia raised US$450 million (RM2 billion) from IPOs and is in pole position, even thumping Thailand (US$427 million), Indonesia (US$248 million), the Philippines (US$194 million) and Vietnam (US$37 million). Singapore raised the least (US$20 million).

While Malaysia held 33% of market share in terms of proceeds raised for the quarter, Deloitte however highlighted that the amount was a drop compared to the same period last year when Malaysia raised US$510 million then.

And in terms of number of IPOs, Indonesia still led the pack with 25, followed by Malaysia with 21, Thailand (17), the Philippines (2), and one each for Vietnam and Singapore.

The Deloitte report said new listings were skewed towards smaller deal sizes, and Malaysia’s IPO performance continued to be underpinned by new listings on the secondary ACE Market.

And the reason is simple: the ACE market allows for companies which can’t meet the stringent regulatory requirements to list on the Main Market.4

Despite the buzz, Bursa still has its fair share of challenges. The LEAP market – targeted towards small and medium enterprises and for sophisticated investors5 – is struggling, with only one listing last year and this year.

And to think, LEAP was the first of its kind when Bursa Malaysia rolled out the platform in 2017. Other similar markets in the region include South Korea’s Konex and Taipei Exchange’s Pioneer Stock Board.

The low number of IPOs, coupled with low trading volume, on LEAP prompted the Bursa Malaysia to review the platform in a move to make it more competitive.

The Securities Commission is also working on getting more companies to list on the Main Market. Its accelerated path for ACE-listed companies to transfer to the Bursa helps firms move up within a month.

But hopefuls must meet seven stringent requirements, from having an RM1 billion market cap to registering an uninterrupted profit of three to five financial years.

Despite the higher bar, a number of ACE companies have expressed interest. Successful ones include electronics manufacturing services firm Nationgate, which transferred its shares from the ACE to the Main Market in May this year.

But is it an ideal exit choice for tech firms such as Carsome? Bursa is currently typified by hefty institutional presence, some family conglomerates and a list of goreng6 counters.

Given the challenges as are the opportunities, the Bursa Malaysia remains an option but it isn’t for everyone. I’m on the fence on this one.

Talk to me

Have a burning question or a tip-off? You can always reach me at: emmanuel@themalaysianist.com.

MCMC published the information paper and the FAQs here for public scrutiny. It’s worth checking out, more so as the agency put out an ambitious claim to hold a wide-ranging stakeholder town hall.

EO 2000 and LR 2000 refer to the Communications and Multimedia (Licensing) (Exemption) Order 2000 and the Communications and Multimedia (Licensing) Regulations 2000, respectively.

It’s not quite apples-to-apples between 99 Speedmart and 7-Eleven, but it’s the closest benchmark I could find, based on the former’s IPO prospectus.

There are three platforms to trade on the Bursa: Main, ACE and LEAP. ACE and LEAP are acronyms for Access, Certainty and Efficiency and Leading Entrepreneur Accelerator Platform.

To list on the main market, a company needs to have a combined track record of 20 million ringgit in profit for the latest three to five financial years. The profit in the latest financial year should be at least RM6 million.

The Main Market is regulated by the Securities Commission. ACE and LEAP, on the other hand, are regulated by the Bursa and have less stringent measures.

Companies listing on ACE are not required to provide a track record of historical profit but need to have a paid-up capital of between RM5 million to RM10 million.

LEAP, introduced in 2017, is designed for SMEs that do not meet the paid-up capital requirements of ACE. Companies looking to list here are also not required to furnish a profit record but need to ensure they are solvent as per the standards set by the Malaysian companies’ act.

But LEAP is only accessible to “sophisticated investors,” which the bourse defines as entities with net assets exceeding RM10 million or individuals with net personal assets exceeding RM3 million or whose gross annual income exceeds RM300,000.

Colloquial term for penny stocks, those that rise and crash quickly as you can say roti canai. These stocks usually benefit syndicates and sharks.