Fashionable musings, Pt 2

And a short note on the late Daim Zainuddin.

Former finance minister Daim Zainuddin died this morning. He was 86 years old. For those of us who covered Malaysia’s political economy, Daim was one man on everyone’s radar, since he was also a major corporate player. He made friends and he made enemies.

I’m not sure if I should write something about him since he is the ghost of the past. And we desperately need to move on from the ‘90s political feud between PM Anwar Ibrahim, his mentor-turned-nemesis Mahathir Mohamad, and the villain in Anwar’s books, Daim.

Because it’s that particular power struggle that has come to haunt us time and again and has shaped both Malaysia’s corporate and political spheres till today — not for the better, I must say.

But at the same time it’s that feud that has defined a lot of the corpo-political dynamics we see today.

The three of them were in Mahathir’s government. Daim first came in as special adviser to Mahathir, in a move that many saw as a way to circumvent Anwar, who was then deputy PM and finance minister.

Anwar and Daim also never saw eye to eye when it came to matters relating to Corporate Malaysia.

When Anwar was in the political wilderness, Daim raised a coterie of men called Daim’s boys, where a number of them would be the subject of bailouts following the 97-98 Asian financial crisis.

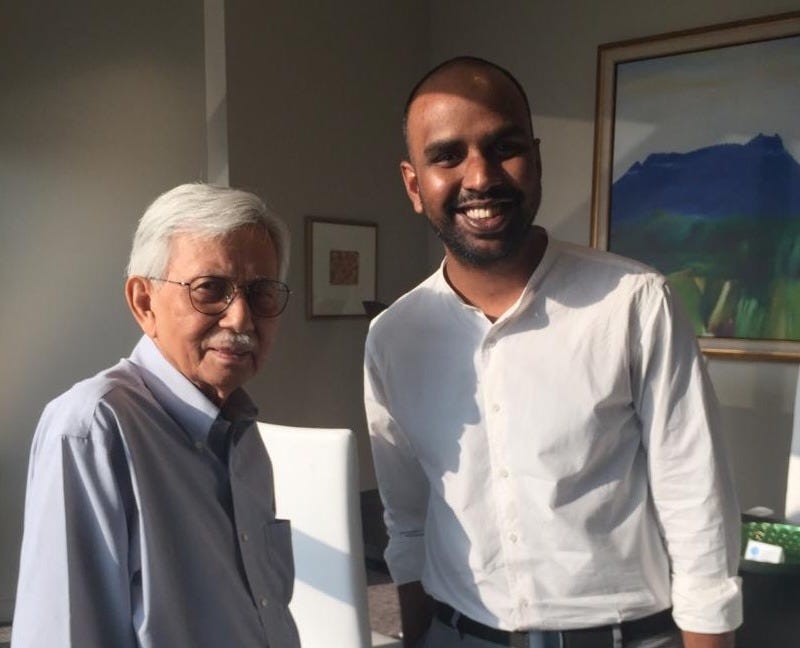

I interviewed Daim when I worked at business paper Focus Malaysia in 2019. That time he waltzed in with his usual oversized baby blue shirt, black slacks and black flip flops.

He was punctual and just like his former boss, Mahathir Mohamad, would have some notes prepared, but was willing to take on any question.

There’s a hilarious video going around of a bunch of young Malay men, prancing around Dataran Merdeka in Kuala Lumpur, in what they call “casual old money” wear.

They were clearly seeking attention. But I also guess it’s symbolic of the kind of ignorance we have today towards old money folk.

I’m not sure if Daim, too, is old money in that sense (maybe his kids and grandkids) but he accumulated wealth so great, he owns a skyscraper in the heart of KL. At the top, which is his office, you get a stunning vista of the capital, an emperor’s view.

And he made all his deals and interviews there, in his classic “grandfather” getup.

Menara Ilham (or Ilham Tower) was the kiblat (direction) for many corporate and political elite.

Tycoons such as Berjaya's Vincent Tan as well as the so-called Daim's boys, which include the likes of Halim Saad, owe their success to him.

Now they will have to look elsewhere. I doubt it’d be Sungai Long or wherever PM Anwar Ibrahim calls home.

During that interview, Daim was Daim. He still had a penchant for banks. His mind was moving back and forth on the latest deals, especially agriculture and agri-tech. He also had inside information on the country’s mega projects since he chaired the Council of Eminent Persons (CEP), an extra-parliamentary body which should not have been allowed to operate in the first place.

I left the interview thinking that a person like Daim shouldn’t exist. No one should be allowed to amass so much wealth and go unchecked, unfettered. His empire stretches overseas and remains opaque. His children held his wealth while they were still kids, in offshore accounts.

But, at the same time, while he wasn’t a creature of the New Economic Policy, he still depended on political patronage — owing his first business break to the late Selangor MB Harun Idris who helped him secure land for a development project.

This is in many ways telling because no Malaysian corporate giant is self-made after all. And you can even see this even in “young” areas like startups where Malaysian VCs are trying to milk their exit by partnering with politicians, royalty or cronies. It’s the Malaysian DNA.

Daim’s death comes at a time when the patriarch and his family are being investigated by the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) over the staggering wealth they accumulated through the years which made the Pandora Papers exposes.

PM Anwar, however, parried criticism that he was out for vengeance.

Whichever way this goes, Daim left a mark. “I’m not too concerned about what historians or journalists will write about me. I’ll leave it to them to judge me,” Daim told me that day. Guess, I’ll just leave it at that.

From the archives:

You’re reading a paid version of The Malaysianist, a newsletter on money and power by writer and journalist Emmanuel Samarathisa.

I run monthly and annual subscriptions. There’s also the atas or founding member tier where you get all the perks of an annual subscription and more, such as an annual report and insight into how this little corner of the internet fared throughout the year.

Group subscriptions are also on the table, too, if you’re mulling over bulk purchases for your organisation or family members.

On Monday, I published a backgrounder on FashionValet and that, for now, despite all the fracas around the company, everything that’s being scrutinised is from the group’s books.

That means the numbers were privy to people other than founders Vivy Yusofy and Fadzarudin Shah Anuar. More importantly, the board and shareholders were in the know when it came to major business decisions.

Were the board members misled? That’s something we’ll have to keep watch as the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission (MACC) is continuing its investigation into the fashion firm, focusing on the money flows received by the founders.

For what it’s worth, post-2018 (obviously an aftermath of the 1MDB scandal), the MACC has better tech to trace fund flows as long as they are circulated within Malaysia, according to legal sources I spoke to for this newsletter.

So once they (MACC) are on to you, and as long as you don’t move money offshore (different jurisdictions and all), there’s no running away.

I digressed a little there. To wrap up Monday’s post, here are seven observations. I might gloss over some terms or assume that my readers know what I’m talking about, since I do cover startups and venture capital for Singapore-based Tech in Asia. Apologies in advance if I sound strange.

Here we go: